This article contains affiliate links.

Several years ago, I attended an Appleseed shoot in Santa Barbara, California. I forgot the specific circumstances, but I was complaining about something or other with my shot cadence on the second day. The shoot boss looked at me and asked, “Can you run a mile without stopping?”

I was flabbergasted at such a question. Of course I could run a mile without stopping. I ran three to four miles every Friday with my unit in addition to the rest of my workouts. After nodding with a sheepish smile, he suggested I take two shots with each cycle of my breathing.

That moment stuck with me for a long time. Not because the advice was profound or anything like that, but because it seemed like such

In the many years since that moment, I’ve attended so many competitions and training events that the idea solidified in my mind. The vast majority of people involved in the world of the Martial Marksman are completely falling short in their physical fitness. I see that as a problem.

Physical fitness and shooting go hand in hand. There are too many people in our community who only focus on the shooting and gear components while completely ignoring their own health.

Several trainers have made a note to point this out, but the only people nodding along are those who didn’t need to hear it in the first place.

Well, this is my soapbox.

Introduction

Let me be up front. I am not a certified fitness expert. I’m not here to prescribe a workout plan for you. Nothing I say here should be considered medical advice, and you should check with an actual medical, exercise, or nutritional expert if you want those kinds of answers. That said, I am a nerd for data and

I originally wrote this article in October 2018, and this revision seven years later (September 2025) reflects additional years of thought, experimentation, and learning on my part. I’ve worked through piles of books, nutrition plans, and research from the actual professionals to see what works for me. I’ve also interviewed many trainers and exercise physiologists in my journey. So this is a brain dump, of sorts.

Finding the Why

So let me start with something simple, a source of motivation. Everything in your life is easier and better when you’re in good physical shape. I’m not just talking about whatever hardship like Scenario-X throws at you, either.

I mean the way people treat you in your day to day life. Fit people, especially when they are older, get more respect. They are perceived as more capable, professional, disciplined, and more “put together.”

I also mean the ability to keep up with your kids, and grandkids someday. It means being free to sit on the floor and get up again without pain. Fitness translates to walking up flights of stairs without getting out of breath, carrying the groceries in one trip, and being strong in the face of adversity.

Lastly, people in good physical condition are more intimidating. I mean this in a good way. Should you find yourself in a bad situation, criminals are more likely to avoid escalating violence against someone who looks like they would put up a fight or prevail. In a “collapse” situation, a group of physically fit people is a more difficult target than a bunch of soft looking dudes in poorly fitting kit. It stands out, and factors into the deterrence calculation.

That’s what it all means to me.

Now “Doing” is more difficult than “knowing,” so my path is filled with setbacks, lack of discipline, and struggle. In the end, this is what teaches the long term lessons. What I’m dumping on you here is a whole lot of “knowing,” with a pinch of my experience. I hope you use it to dig further.

Defining Tactical Fitness

What do I mean when I refer to “Tactical Fitness,” anyway? What distinguishes it from any other fitness routine like bodybuilding, powerlifting, Crossfit, or other endurance sports?

First off, tactical fitness is not the silly stuff you see on YouTube. Flipping tires while wearing a plate carrier and then shadow boxing while heavy metal blasts in the background. That can be fun, and makes great social media fodder, but the real definition about a bigger picture.

Stew Smith, former Navy SEAL and long time fitness writer had this to say:

Tactical Fitness is not about workouts, it’s about work. It is not about working out to get good at working out, it is about creating programs that carry over into real life movements like lifts, carries, crawls, runs,

rucks, swims, and mobility. Even analytical and creative thinking. It uses non-traditional equipment to lift and carry loads that are not equally balanced.

I like that definition. Let’s start there. When I talk about Tactical Fitness, it’s about a mindset focused on being generally capable across a wide variety of skills and requirements. It is the opposite of specialization.

Tactical Means General

Jeff Nichols, a former SEAL

A tactical athlete has to be good at everything without putting too much emphasis on any one area. It’s a jack-of-all-trades mindset. Take this list from Stew Smith for instance:

- Speed and Endurance – You need to be able to run, ruck, and sprint depending on the situation. You will continue doing this for hours to days if needed.

- Strength and Power – You need to be able to carry gear, drag or carry your buddy, pick yourself up over obstacles, or move things out of the way

- Flexibility and Mobility – You need to move over uneven terrain, without injury, drop into awkward or tight positions, and quickly get back out again to sprint to the next position

- Muscular Stamina – You’re going to have to exert muscular force again and again and again. Bad things don’t stop happening just because you’re tired.

It is very common for an advanced Tactical Athlete to be strong enough to do 20 pull-ups and

deadlift two times his bodyweight of 200 or more pounds and still be able to run a six-minute mile pace for several miles. Those are excellent numbers, but a cross-country runner will beat you by a minute in a mile run, but likely fail at strength events. The strong man will almost double your lift weights, but take a bus when the mile run is tested.

Professional Athletes Are Too Specific

Think of a professional athlete in any sport. The reality is that they are probably a master in only one or two of these areas. Football players demonstrate immense amounts of power and force during repeated intervals. But the average player is only in motion for 11 minutes total during a four-hour game.

Basketball and soccer players move more than that at 3 miles and 7 miles per game, respectively but they don’t generate the power and force needed for football.

A tactical fitness program means that you will not reach elite levels of fitness in any one area, but that you are very capable in all of them. It’s not just about strength, power, speed, endurance, or stamina. It’s everything.

To go back to one of my principles of the Martial Marksman: there is no optimum. Saying something is optimum means you know the exact outcome you’re aiming for. In athletics, that means knowing a specific set of universally-enforced rules, a specific set of movements and required skills, and a defined period of time in which it happens. Real life, especially in conflict, doesn’t work that way. But it is, athletic. As my friend Ross, a former Ranger, likes to say: “Combat is an athletic event.”

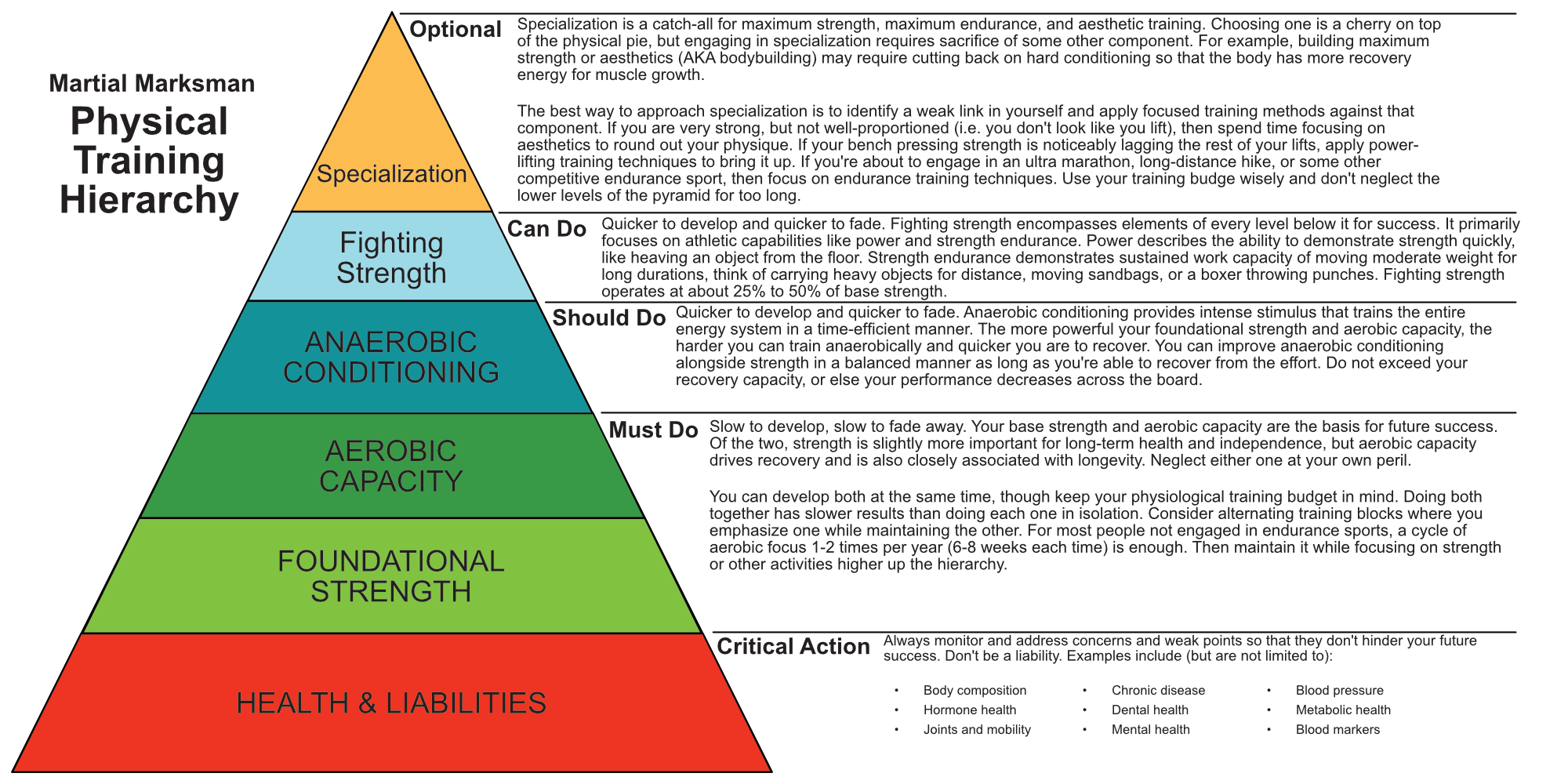

To illustrate my prioritization, I created the Martial Marksman physical hierarchy.

Back to the Pyramid

I will not belabor the hierarchy because I explained in detail elsewhere. The very short version is that we divide Tactical Fitness into different levels of prioritization. The very foundation is your general physical health. These are markers like your body composition, blood pressure, mental health, and any chronic disease.

High level competitive athletes eventually get to a point where they willingly make trade offs to their physical health in order to compete at the desired level. Think of professional football players who accept traumatic head injuries as part of the game, or professional bodybuilders who wreck their hormones and heart health with anabolic steroids.

Your goal should be never sacrificing your physical health unless absolutely necessary, such as in actively saving your life or that of a loved one. Until then, always play the long game of maintaining or improving good physical health so that it supports your training goals.

From there, the pyramid goes up. Everyone must develop a base of raw strength. This does not need to be as high as you think it would be, but it is there. Being stronger makes every other pursuit easier and more powerful along the way. Just as important is a foundation of aerobic capacity. This isn’t just “cardio,” but rather your body’s ability to deliver oxygen to where it’s needed, process and support your energy needs, and efficiently clean up any metabolic waste products.

Despite what powerlifting pop culture says, aerobic training goes hand in hand with strength training for the vast majority of people.

The next levels up focus on your ability to energetically sustain and recover from very intense short bursts of effort. Think of sprinting, fighting, dragging a friend out of danger. That anaerobic capacity then flows into “Fighting Strength.”

Only at the very top do we reach the specializations. For most people, most of the time, the specializations are completely unnecessary. Specialization requires trade offs that impact the levels below the peak, all the way down to the foundations. You can do it for a while, but eventually you’re going to pay for it.

Complicating Factors

There are several more characteristics to a tactical athlete that you need to consider. These things further separate them from other athletic pursuits found in the gym.

First, tactical athletes do not have seasons. There is no offseason where you can let yourself go a bit. Law Enforcement officers, for example, are on the job all the time. Any incident in the law enforcement world can rapidly escalate to life-threatening in a matter of seconds. If that’s your job, then you are always on your game. This is the world that most civilians and Martial Marksman find themselves in.

You might think military members are more like athletes training for a specific season- and you’re not entirely wrong. But even in that case, athletes train for specific movements and a set of known rules and conditions. Military deployments are physically demanding, yes, but also unpredictable.

The Burden of Constant Fitness

The need to maintain a high level of fitness all the time requires a lot of discipline and focus. It requires getting away from a purely goal-oriented mindset where you are training towards something. That kind of mindset means that there’s a logical end point where you no longer need to keep working.

Instead, you train because that’s who you are. You focus more on the process than the outcome.

Another factor pointed out by Jeff is that the average tactical athlete is much older than the average professional athlete. Military members, law enforcement, and other first responders have careers spanning decades. They are much less tolerant of injury or downtime. Not being able to work means not getting paid. Staying fit and strong without injury as you get older gets more difficult.

I’ve been relatively lucky in this area. I’ve only had a smattering of broken bones and sprained ankles in my life. But I’ve got friends who’ve torn their back muscles, shattered spinal bones, had knee surgery, and a variety of other problems. These all add up over time, and it makes it that much harder to maintain a fit lifestyle.

You need to train with these truths in mind:

- You’re not training towards a season or game, you’re training for life

- You need to train in a way that’s sustainable for the duration of your life

So what does a Tactical Fitness Program Look Like?

I asked the

From a fitness programming perspective, a tactical athlete’s fitness must cover a much more broad array of fitness demands…Their fitness demands are much more “multi-modal”. Green athletes, for example, need high relative strength (strength per bodyweight), high sprint-based work capacity, tactical agility, endurance (running/rucking) and chassis integrity (core). Most tactical athletes cannot predict the tactical situations they face, and thus their programming must be broader and embrace more fitness attributes than more narrow sport or competition athletes who can predict what they will face in competition, and program accordingly.

Grouping By Tactical Needs

Rob mentions “Green Athletes” in the statement. I asked about that, and he broke down all of his tactical programs for me based on color coding.

- GREEN – Military Infantry, Land-Based SOF (Green Beret, Ranger, Delta), Wildland Firefighter, and LE units with rural mission sets – BORTAC, FBI HRT, many rural state SWAT/SRT

- BLUE – Military and LE units/teams who’s mission sets include water – Border Patrol BORSTAR, MARSOC, SEAL, DEVGRU, USAF CCT/PJ/CRO

- RED – Fire/Rescue

- GRAY – Urban-based, full-time LE SWAT and SRT

- BLACK – LE Patrol / Detective

What I found very interesting while talking to Rob was that he still emphasized some sport-specific training based on needs.

Each of these tactical athlete categories has a unique set of mission-direct fitness demands. Some of these demands overlap between categories, and some don’t. For example, Green athletes (Military Infantry) have a far greater endurance demand (running, rucking) than Black (LE Patrol/Detective). Blue Athletes

share all of the fitness demands with Green, but also need swimming on the endurance side.

The vast majority of civilians and Martial Marksman are probably well served by something geared towards the Black or Gray category. It means, a good amount of strength, enough endurance and mobility to chase someone down in a foot pursuit, and explosiveness to advance during a firefight. These capabilities have overlap, though, so transferring capabilities to a new “mission set” like long distance rucking wouldn’t be difficult to do.

It’s Not About Big Muscles

On an old episode of the podcast, Mike and Kurt at Fieldcraft-Survival had a discussion about their experiences at Ranger School. I remember them talking about “Ranger Body.” They weren’t talking about it as an ideal, though.

“Ranger Body” was the generic look that everyone had when they finished. The guys who showed up with huge muscles lost them as time went on. The body is smart, and recognized that carrying huge amounts of muscle mass required a lot of calories to maintain and negatively impacted endurance. Their bodies cannibalized that muscle for energy and to make survival in austere environments easier.

On the other hand, the guys who showed up weak…well, they didn’t make it.

Jeff Nichols and Stew Smith had a similar discussion about aspiring SEALS training for BUD/S. A 270 lb bodybuilder who wanted to be a SEAL asked them what weight he needed to get down to in order to succeed. They told him to get below 220. Even at that lower weight, he would still be one of the biggest guys there.

Mass Is Not Always the Answer

More muscle mass is not always beneficial. Muscle mass means more metabolism byproducts to deal with. Mike and Kurt talked about the smell that the huge bodybuilders emitted as their bodies cannibalized muscle protein for energy. More muscle mass means you have a larger caloric demand, and in austere environments like that simply don’t support it.

In reality, it’s almost impossible to maintain a very large physique if you don’t have access to the number of calories you need to eat every day to maintain it.

Strength is important, but there are diminishing returns.

So how much should you weigh? I have a more thorough write up on that, but here’s a quick rule:

Take your height in centimeters. Subtract 100. This is your target bodyweight in kilograms while also staying relatively lean at 15% body fat or below for men.

Example: If you are 6'1" (73") tall, that is 185.42 cm.

185.42 - 100 = 85.42

85.42 kg = 188.3 lb

So, you would aim to be about 188.3 lbs while also keeping your body fat percentage to 15% or below. The Long Game

Jeff Nichols points out that always training to your limits and “worst case scenarios” means you’re not really training. You’re just exhausting the system. The simple truth is that you can’t do that to yourself all of the time, especially when you still have a job to do. If you can’t rescue your buddy because you had a killer leg day, then you are working against mission requirements. If you destroyed your energy reserves so much that you can’t effectively train anymore, then you are wrong.

You can’t keep adding stress without end. Your body only adapts to stimulated stress so quickly and for so long before it gets injured or worse.

I ran into this one myself while following Mark Rippetoe’s novice linear Starting Strength program. I made significant progress on my basic foundational strength, but eventually started getting injuries in the form of back tweaks and aching joints- a sure cue that I should have moved on to a more appropriate training style. You have to account for your ability to recover.

Patience, You Must Have Patience

Fitness is not a linear progression. Jeff talks about it like the stock market. It has ups and down, sometimes big downs, but the long-term progression is up.

That is, provided you planned for the long game and invested wisely. I also like what Dan John says about training smart: “Everyone has one more injury in them. The question is, do they have another recovery?”

Setting Tactical Fitness Standards

Before I talk about what a Tactical Program looks like, let’s talk about standards. What should a trained tactical athlete be able to achieve?

Most people think that a good place to start is a military fitness test. I totally understand why, but I also don’t think that’s a good path. From experience, the military fitness tests are not designed to test your capabilities. They are designed to weed out people who become health problems.

If the Air Force’s fitness test was the measure of tactical fitness, then everyone would look like skinny cross country runners without any upper body strength. That’s not ideal, and everyone in combat arms knows it. That’s why the Army devised yet another combat fitness test and the Marines have something similar.

Tactical Fitness Testing

Rob Shaul mentions that a tactical athlete has a high relative strength. That means that they are strong relative to their current weight. Here are Rob’s basic strength benchmarks:

| Lift | Men | Women |

| Front Squat | 1.5 x Bodyweight | 1.0 x Bodyweight |

| Deadlift | 2.0 x Bodyweight | 1.5 x Bodyweight |

| Bench Press | 1.5 x Bodyweight | 1.0 x Bodyweight |

| Push Press | 1.1 x Bodyweight | .7 x Bodyweight |

| Hang Squat Clean | 1.25 x Bodyweight | 1.0 x Bodyweight |

| Squat Clean + Press | 1.1 x Bodyweight | .7 x Bodyweight |

| Pull Ups | 16 | 8 |

If you compare Rob’s numbers to Strengthlevel.com, a commonly used metric in the powerlifting community, his strength standards would put you in the “intermediate” category.

What does that tell you? Tactical athletes need to be strong, but not elite.

Becoming elite means sacrificing in too many other areas.

That said, Tactical Fitness encompasses so many aspects that you can’t just focus on the strength part.

The Big Picture

With everything I’ve learned over time, I put together my own calculator to provide goals and targets. It’s free for you to make a copy, and you can find a link in that article. But here are some target to aim for.

- Body Composition

- Waist measurement that’s 0.45 to 0.47 of height

- Body fat percentage below 15%

- Strength (1 Rep Maxes)

- Overhead Press: 0.8 to 1.0 x bodyweight

- Bench Press: 1.25 to 1.5 x bodyweight

- Squat: 1.75 to 2.0 x bodyweight

- Deadlift: 2.0 to 2.5 x bodyweight

- Weighted Chin Ups: additional 0.4 to 0.6 x bodyweight

- Fighting Strength

- Broad Jump: 1.3 to 1.6 x height

- Power Clean: 1.5 x bodyweight

- Farmer Walk: 0.5 to 1.0 bodyweight per hand for 25 yards

- Squat: 1.0 x bodyweight for 15 repetitions

- Bench Press: 1.0 x bodyweight for 15 repetitions

- Chin-Ups: 20 repetitions

- Double Kettlebell Front Squat: 32kg per hand for 20 repetitions

- Kettlebell Snatch: 24 kg for 200 repetitions in 10 minutes

- Conditioning

- Running: 8 minute per mile pace for up to 5 miles

- Rucking: 0.25 x bodyweight for 8 miles in less than 2 hours

- Assault Air Bike: Bodyweight in calories within 10 minutes

Aside from that list, I also have a series of fitness assessments for you to engage with and see where you stand. I keep these updated over time as my ideas shift and I learn more.

Tactical Fitness Programming

Let’s talk about what a year-round program looks like for the tactical athlete. If you’re looking to maintain a solid level of fitness across all the required areas, then you need to break that up into sections. You simply can’t work on all of it at the same time. Your body cannot adapt that quickly in all those different directions.

The professionals break up their training into periods throughout the year.

Periodization for Tactical Fitness

Jeff Nichols talks about alternating between strength and speed, with conditioning work thrown in throughout. He has his athletes work on strength and power for six to eight weeks to grow new muscle. Then, he spends another six to eight weeks making those muscles faster.

Rinse and repeat.

Stew Smith published his year-round periodization.

- January – March: Near 100 percent weights, more non-impact cardio workouts. Ruck / Swim with fins.

- April – June: Calisthenics and cardio workouts. Run / Swim Progression

- July – September: Calisthenics and cardio workouts (advanced). Run Max / Swim Progression

- October – December: Calisthenics, weights, and decrease running / non-impact cardio workouts. Ruck / Swim with fins.

If you look over Rob Shaul’s programs, you see a similar trend of alternating every three to eight weeks between strength focus and speed focus. Conditioning is always present, so it’s a matter of sport-specific focus.

For me, I tend to spend the fall and winter focusing on strength & mass, the spring on strength & conditioning, and the summer on strength & power. I like to think of summer as “competition season” for things like tactical biathlons and Run & Gun.

“But Matt,” you ask, “won’t you lose your gains in strength is you stop working on it?”

The answer is you might lose some of that maximal power or speed output that you build up during any period but won’t slip back to where you started. As this cycle repeats year over year, you

Tactical Fitness for Beginners

I asked the coaches about the biggest mistake most people make when it comes to their programs.

The answer: Not picking a program and sticking to it.

Beginners are especially bad about this because they have no context. Any untrained individual sees some very quick results no matter what training program they use. This is not because they are getting stronger or quicker in a matter of weeks

As a newbie starts exercising, the brain and nervous system look for ways to be more efficient. The body learns to recruit muscle fibers more efficiently, which helps the newbie lift more weight. That rate of progress is not sustainable in the long term.

Eventually, as your nervous system figures out the movement pattern, the limiting factor actually becomes your strength and conditioning. Getting that to change takes time, effort, recovery, and patience.

Embrace the Plateau

As a beginner hits the plateau, where the gains slow down and they get frustrated. Beginners then quit the program and look for the next new thing to work on. Maybe that new thing brings some quick gains, but they will eventually run into the same problem.

The key for beginners is to pick a program and start working. Stay on the program until it ends, and then start over or pick a new one. Always stick to a program.

Jeff Nichols expressed that a lot of newbies don’t exercise with intention. They randomly pick movements and exercises and call it a workout. If you pick random workouts over time, you have random results. That’s not going to work.

Trust the professionals here, and pick a qualified program to follow. I always like to keep 4-6 “reference lifts” in the mix throughout the year that I’m actively tracking progress on. These lifts, which are typically big compound movements, may not be in every training block, but they are never far away.

Structuring A Plan

Ok, I get that I’ve done a lot of pontification and given advice without a concrete example. So let’s take a look at an example. I mentioned that I tend to break my year up into 3-4 “seasons.” For the most part, these seasons look very similar to one another, with the main variable being how I distribute my days between strength and conditioning.

Let me preface by saying that I commit to training six days per week, Monday through Saturday. I’m up at 5 AM every Monday to Friday so I can be in my garage gym by 5:30 AM. On Saturdays, I’m typically still up by 6 AM and the workout may be around 10:00 or 11:00 after I’m awake and fed, and these workouts tend to be longer and more brutal since I have the next day completely off.

Here are some example blocks, each one done for 12-16 weeks at a time (including planned “easy weeks” where it’s the same stuff but a bit lighter and less of it).

November to March

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barbell OHP Close Grip Bench Lying Tricep Ext. Cable Rear Delt Fly DB Lateral Raise | Squat Single Leg RDL Weighted Chin Up T-Bar Row Barbell Curl Calf Raises | 30 Minutes Zone 2 Run/Ruck/Cycle/Row + Abs | Bench Press Seated DB Press DB Lateral Raise Incline DB Press Dips Chin Ups | Assault Bike Sprints + Abs | Deadlift SSB Squat Lunges T-Bar Row BB Curl Calf Raises |

Then, from April to June

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bench Press Squat Weighted Chin Ups Barbell Curls | 30-60 Minutes Zone 2 Run/Ruck/Cycle/Row | Overhead Press Deadlift Dips Tricep Extensions | Tempo Work for Time Run/Ruck/Cycle/Row | Bench Press Squat Weighted Chin Ups Lateral Raises | Kettlebell Snatches + Heavy sandbag picking/loading |

From July to October, I consider myself “in season” for events like Run & Gun or other competitions.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bench Press Squat Weighted Chin Ups Dips | Kettlebell Snatches + 20 Minutes Zone 2 | Assault Bike Sprints | Bench Press Squat Weighted Chin Ups Rows | Tempo Work for Time Run/Ruck/Cycle/Row | Deadlift / Power Cleans Overhead Pressing – or – High rep strength circuits |

That gives you a general idea of what I might structure throughout the year. This is not strictly what I do, it’s just an example of how you can break things up to have a different emphasis. Sometimes more strength days, sometimes more conditioning days, sometimes it’s balanced.

You should assume that there are detours for other things, like maybe 6-8 weeks at one point dedicated to a specific style of workout or focus like cleans, strongman, or calisthenics. I might also swap around exercises from time to time by switching to an incline bench press rather than flat, or front squats instead of back squats- but that’s all in the nuance. The point is that it’s always six days per week, and you see the same movement patterns over and over again.

I’m a fan of kettlebell snatching because of the ballistic movement. The act of quickly hinging and accelerating a weight overhead is a good way to both get conditioning, but also train those fast twitch muscles that often get left behind in slow grind strength training. Also great are plyometrics and the Olympic movements.

Tactical Fitness for Athletes Over 40

So what if you’re not a beginner, but you’re getting older? I first wrote this article when I was 34, and now I’m pushing 42. It’s more relevant than ever to me. First, it stands out a whole lot when someone over that 40 mark is in great shape. It’s relatively easy for someone in their 20’s without a lot of life responsibilities and obligations to be in good shape. When someone is older and still “has it,” people sit up and take notice.

Kelly Starrett says that the human body is built to last over 100 years of proper operation. The fact that most of us start to fall apart long before that is because of our own poor lifestyle habits and movement patterns.

Jeff Nichols emphasized that an athlete can train to a certain point with bad movement patterns, but eventually those poor patterns hold them back.

The overall fitness pattern for those of you over the 40 mark like me doesn’t look all that different than it did in your 20’s or 30’s. Fitness is fitness. But you are also slower to recover from injury and hard workouts. That means you need to focus on correct movement patterns and recovery.

That includes getting the proper amount of sleep.

I highly recommend Kelly Starrett’s book on movement patterns, as it tremendously helped me get over some lingering ankle and back injuries.

Monitor What You Eat

Aside from movement itself, those of you over 40 have probably realized that you can’t out exercise a bad diet. I can’t tell you the number of times I was in a military gym and overheard the young bucks in their early 20’s talk about “Working out so we can go out tonight.”

As I got older, I seriously noticed the impact of a single bad night of eating or drinking on the quality of my sleep. Poor decisions lead to poor sleep, which meant crappy training the next day (or more), which means slowed (or no) progress.

Play the Long Game

Andy Baker and Dr. Jonathon Sullivan once made an analogy of the effects of aging to a flowing river. Strength training is like fighting against the current. The harder and more consistently you work, the better progress you make. When you stop training, the water pushes you backwards.

Aging is the speed that the water pushes against you. As you get older, the water pushes faster. In effect, any break in training from injury, sickness, or lifestyle habits has more dramatic setbacks as you get older. This is why it’s so important to pay attention to recovery and correct technique. You could get away with an injury in your 20’s and bounce back relatively quickly without much loss in progress. In your 50’s and beyond, that setback may be unrecoverable.

Play the long game, and always plan to train another day.

It’s not just about being tactical.

Look, here’s the bottom line. Tactical Fitness is a buzzword, just like General Physical Preparedness was a several years ago. This whole idea is about adopting a year-round fitness program that continually improves all areas of your physical capabilities. Moreover, it’s about doing it without a particular goal in mind. This isn’t really about being “tactical,” it’s about being a healthy human.

I simply cannot stand the idea of being like some of my relatives who ignored their bodies for decades, and now they struggle with seemingly simple physical tasks. Someday, I want to be the old guy who can still run around the playground with the grandkids (hopefully). I want to be the epitome of the “badass old man” that you don’t want to mess with.

But that doesn’t start as you get older. That starts with a proper strength and conditioning program right now, or last year, or ten years ago.

But What About Events

So where to physical challenge events like GoRuck, Spartan Races, Marathons, Tough Mudders, Twilight Run N Guns, and others fit into all of this?

These events are ways to test yourself among a fairly narrow set of skills. GoRuck, for instance, is about sustaining moderate intensity over extended time. Tough Mudders and Spartan Races are endurance races with some extra strength thrown in.

Treat these things as they are: sporting events.

Simulations are Not the Real Deal

When I asked the coaches about these things, they really didn’t have a particularly strong opinion. They see them as artificial constructs rather than real challenges. Rob Shaul put it to me bluntly:

I would recommend civilians skip these artificial events, and rather plan and complete real outdoor adventures on their own. I.e., instead of signing up for a GoRuck event, teach yourself to

– Rob Shaulbowhunt or plan a week-long high country backpacking/fishing trip in the Bridger Wilderness. Instead of a Spartan race, plan, train for and complete a Rim to Rim hike of the Grand Canyon.

Does that mean I’m never going to do another GoRuck or Tough Mudder, or some other event? Not at all. I still get a lot out of the social interaction and team building components

All of that said, if you want to do one of these things, then your training will change a little bit. If you think of your year-round programming as your baseline, then one of these events becomes a focal point. You will shift your programming to prepare for one of these events directly. That might mean spending more time under a ruck or doing more climbing work, or other elements that help you prepare.

This is a different subject altogether.

Wrapping Things Up

Fitness doesn’t get any easier to achieve the longer you put it off. The temptation a lot of people fall into is to try and do too much all at once. That’s just a recipe for injury and disappointment.

You need to have patience and discipline. Pick a program, start it, and just keep showing up.

Shooting is obviously a major component of my focus with this site and everything I do. However, I argue that your actual physical base of health and fitness is more important than your shooting skill. You are infinitely more likely to benefit from being healthy, strong, and conditioned in your day to day life than owning the best gear and being a good shot. Take your fitness seriously, as it forms the base from which everything else we do springs forth.

Outstanding article!

Thanks John, that means a lot! I swear I didn’t intend to publish this on the same day as your article, but it just kinda worked out. Article: https://firearmusernetwork.com/2018/10/16/acft-dumb-and-dumber/

I really like what you’ve had to say about the Army’s PT programs.

Great article and very inspiring. This was for me…I’m that guy. I can run and gun, pretty good, for about 100 yds. At training, that’s all I need. Inside the shoot house (it’s big), with kit I’m done for after clearing a 20k sq. ft. house. It’s fatigue and anticipation. Shortness of breath due to stress, combined with the weight of gear and heat.

Time to get busy.

Mark, thanks for reading and commenting! I’m very glad it inspired you. Obviously, from my own numbers I put in the post, I’ve got a lot of work ahead of me as well. I think nearly all of us have fallen into a trap of “eh…I’m good enough” from time to time. But as I approach 40, I really feel like now is the last chance to set up those long-term habits to get me to the 80’s and beyond.

Thanks for the great article. I’m over 50 and life got in the way of my workouts a couple years ago. I need to get back to it. Your article is an encouragement to do something, even if it’s to go hiking/back-packing.

Hey Debbie, thanks for reading! I totally understand. I’ve had moments where the exercise drive just fell off the radar as other things seemed more important. I think it has a lot to do with time horizons. The negative effects of not staying on top of a fitness program seem so far away compared to whatever the immediate issue is.

I love hiking, and it would be my go-to activity if I could get away to great trails on a regular basis.

Very good. Great references that tie it all together. Do you operate a private gym?

Keenan, thanks for coming by and commenting! I do not run a gym or anything, and I wouldn’t want to give that impression. I’m just a research nerd who likes to read and break things down.

Kudos. Can’t wait to read more from you. I’m developing a small business around fitness in my community. With that, I hope to provide quality articles on the subjects I care about, for example influencing young people to take interest in health among other things. WordPress is the platform I decided to try first but, I am a little frustrated with it so far. What platform are you running this site on? Would you mind sharing some tips and such with me to help me build my blog site (website)?

I’m running WordPress, actually. But I’ve been tinkering with web design and blogs for a long time. What kind of things are you struggling with?

Thanks for your service and I want you to reflect on that. I served in the Army and am a police officer and Swat team member and Team leader. I hear “thanks for your service a lot” and I always feel a little guilty about it. It’s not a service, it’s a calling, so there is no struggle in it, and I don’t feel like the ‘thanks” is warranted. Tactical fitness is or should also be a calling in the same way. It is a smart and necessary basic foundation to enduring a career of action, but it should also just be a routine part of the day, the week, the month and the year. Should is the operative word, and your insight, experience and research makes this a lot more possible, so thank you for your prior and continued service.

Ed, thank you very much for dropping by. In an ideal world, staying on top of fitness would be very easy, but life happens. as you said, it should be a routine part of the day. But for a lot of people, myself included, it is sometimes one of the first things to get dropped if the day fills up.

I’d like to think of getting a workout in like hygiene. If you don’t do it, it’s like not brushing your teeth or doing other basic self-care. It just feels….wrong.

I’ve been recovering from injury lately, so I haven’t been on top of things and I’m definitely itching to get back at it.

Matt – great article!

Back in the day I learned this as “practical fitness” – loosely defined as that exercise/conditioning/flexibility/endurance/strength acquired while performing real-life tasks that the individual deems critical to their personal existence. Think along the lines of practicing BJJ – there’s really no other exercise that can better prepare you for fighting on the ground. The physical and mental conditioning, strength, and flexibility also enhance many other aspects of life. But boiled right down – it’s practical strength acquired while learning a practical skill. In todays busy “optempo”, I find it challenging to justify one-off exercises that don’t have practical value otherwise. Running, swimming, biking, combatives, rucking, climbing, etc. are all pretty darn practical abilities.

In the military I learned about the “tactical advantage”, whether it’s taking the high ground, or establishing clear fields of fire from a cover and concealed position, etc. Similarly, in practical fitness I like seeking and understanding “mechanical advantage” (think Archimedes) of a particular activity, i.e. pushing a broken down car off the road – lean-in high on the pillars vs. hand-over-hand roll the tires vs. put your back to the bumper, each is different in terms of leverage and application of force.

Thanks for the write-up and bringing this topic back to the front of my mind.

Tango18

Thanks! This one is probably due for an update and a refresh. I agree with your definition of practical fitness. It’s not so much about vanity, but capability for real-world problems. In the end, for me at least, that’s the goal.

Pat McNamara has a Combat Strength Training plan that really uses this thought process. This year as I start on a journey to recapture some measure of fitness, that’s the real objective.

I have embraced the phrase “You always need to be training for your next birthday”

This is a great article, very inspiring. I’m 55, and was at a crossroads with my fitness, as yes, I’m noticing that I can’t do what I used to be able to do (though I am still the only person in my gym who’s on the battle ropes, hitting the heavy bag and pushing/ pulling the sled, and I’ve actually had people ask how old I am, as they are seemingly amazed).

I was trying to ascertain what my fitness journey should look like, and if I should just train like a (emphasis on drug free) bodybuilder, seeming as I can’t function as “ tactically” as I used to. Reading this article made me realize I can keep doing what I have been doing, with a realization that this aging thing is just a part of the fitness journey.